Introduction

In this tutorial, we'll walk you through the creation of a basic poll application.

In this tutorial, we'll walk you through the creation of a basic poll application.

Let's learn by example.

Throughout this tutorial, we'll walk you through the creation of a basic poll application.

It'll consist of two parts:

We'll assume you have Django installed already. You can tell Django is installed and which version by running the following command in a shell prompt:

python -m django --versionIf Django is installed, you should see the version of your installation. If it isn't, you'll get an error telling "No module named django".

This tutorial is written for Django , which supports Python 3.10 and later. If the Django version doesn't match, you can refer to the tutorial for your version of Django by using the version switcher at the bottom right corner of this page, or update Django to the newest version.

If this is your first time using Django, you'll have to take care of some initial setup. Namely, you'll need to auto-generate some code that establishes a Django project -- a collection of settings for an instance of Django, including database configuration, Django-specific options and application-specific settings.

From the command line, cd into a directory where you'd like to store your code, then run the following command:

cd ~/project

django-admin startproject mysiteThis will create a mysite directory in your current directory.

Let's look at what startproject created:

mysite/

manage.py

mysite/

__init__.py

settings.py

urls.py

asgi.py

wsgi.pyThese files are:

mysite/ root directory is a container for your project. Its name doesn't matter to Django; you can rename it to anything you like.manage.py: A command-line utility that lets you interact with this Django project in various ways.mysite/ directory is the actual Python package for your project. Its name is the Python package name you'll need to use to import anything inside it (e.g. mysite.urls).mysite/__init__.py: An empty file that tells Python that this directory should be considered a Python package.mysite/settings.py: Settings/configuration for this Django project.mysite/urls.py: The URL declarations for this Django project; a "table of contents" of your Django-powered site.mysite/asgi.py: An entry-point for ASGI-compatible web servers to serve your project.mysite/wsgi.py: An entry-point for WSGI-compatible web servers to serve your project.Let's verify your Django project works. Change into the outer mysite directory, if you haven't already, and run the following commands:

cd ~/project/mysite

python manage.py runserverYou'll see the following output on the command line:

Performing system checks...

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

You have unapplied migrations; your app may not work properly until they are applied. Run 'python manage.py migrate' to apply them.

- 15:50:53 Django version , using settings 'mysite.settings' Starting development server at <http://127.0.0.1:8000/> Quit the server with CONTROL-C.Ignore the warning about unapplied database migrations for now; we'll deal with the database shortly.

You've started the Django development server, a lightweight web server written purely in Python. We've included this with Django so you can develop things rapidly, without having to deal with configuring a production server -- such as Apache -- until you're ready for production.

Now's a good time to note: don't use this server in anything resembling a production environment. It's intended only for use while developing. (We're in the business of making web frameworks, not web servers.)

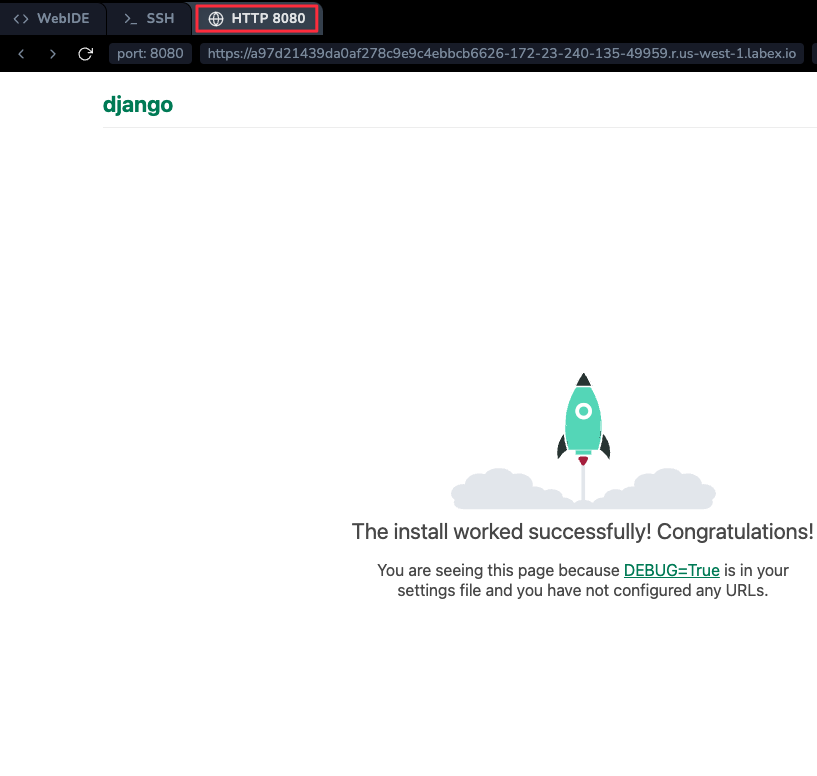

Now that the server's running, visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/ with your web browser. Or, run curl 127.0.0.1:8000 in terminal. You'll see a "Congratulations!" page, with a rocket taking off. It worked!

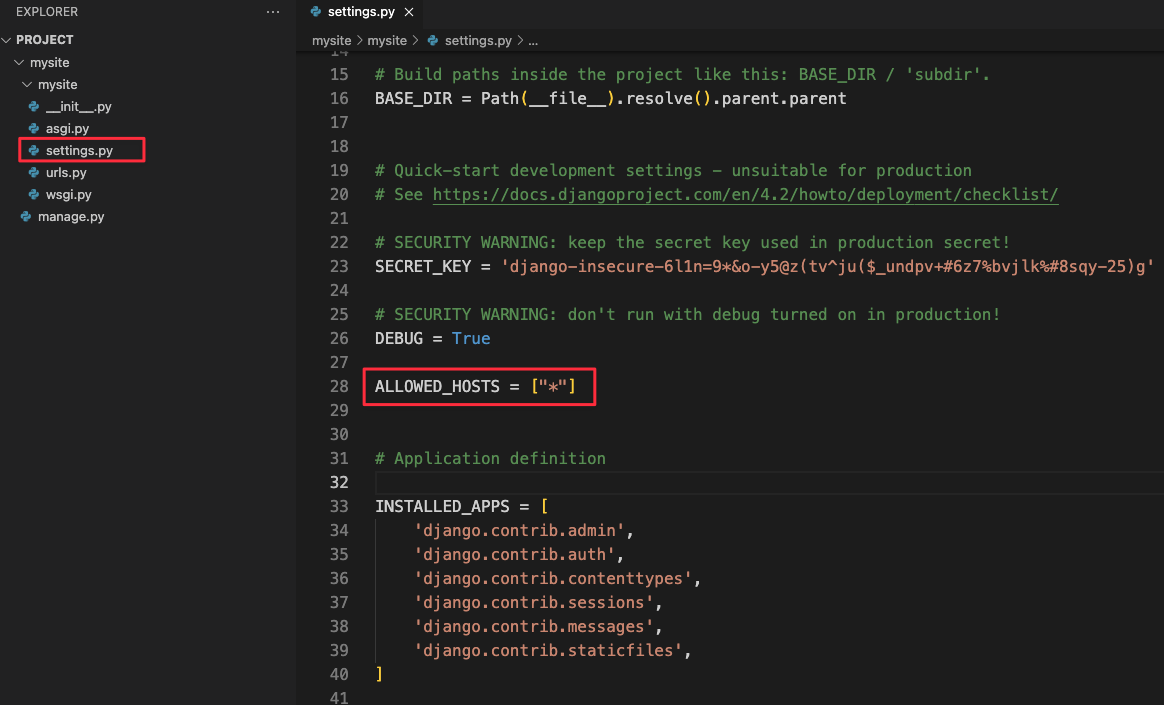

In LabEx VM, we must add need to add the LabEx domain to ALLOWED_HOSTS. Edit mysite/settings.py and add * to the end of ALLOWED_HOSTS, so it looks like this:

ALLOWED_HOSTS = ["*"]This tells Django that it's allowed to serve requests with any host header.

By default, the runserver command starts the development server on the internal IP at port 8000.

If you want to change the server's port, pass it as a command-line argument. For instance, this command starts the server on port 8080:

python manage.py runserver 8080If you want to change the server's IP, pass it along with the port. For example, to listen on all available public IPs (which is useful if you are running Vagrant or want to show off your work on other computers on the network), use:

python manage.py runserver 0.0.0.0:8080Now, switch to Web 8080 tab in the LabEx VM and you'll see the same "Congratulations" page.

Full docs for the development server can be found in the runserver reference.

Automatic reloading of

runserver

The development server automatically reloads Python code for each request as needed. You don't need to restart the server for code changes to take effect. However, some actions like adding files don't trigger a restart, so you'll have to restart the server in these cases.

Now that your environment -- a "project" -- is set up, you're set to start doing work.

Each application you write in Django consists of a Python package that follows a certain convention. Django comes with a utility that automatically generates the basic directory structure of an app, so you can focus on writing code rather than creating directories.

Projects vs. apps

What's the difference between a project and an app? An app is a web application that does something -- e.g., a blog system, a database of public records or a small poll app. A project is a collection of configuration and apps for a particular website. A project can contain multiple apps. An app can be in multiple projects.

Your apps can live anywhere on your Python path <tut-searchpath>. In this tutorial, we'll create our poll app in the same directory as your manage.py file so that it can be imported as its own top-level module, rather than a submodule of mysite.

To create your app, make sure you're in the same directory as manage.py and type this command:

cd ~/project/mysite

python manage.py startapp pollsThat'll create a directory polls, which is laid out like this:

polls/

__init__.py

admin.py

apps.py

migrations/

__init__.py

models.py

tests.py

views.pyThis directory structure will house the poll application.

Let's write the first view. Open the file polls/views.py and put the following Python code in it:

from django.http import HttpResponse

def index(request):

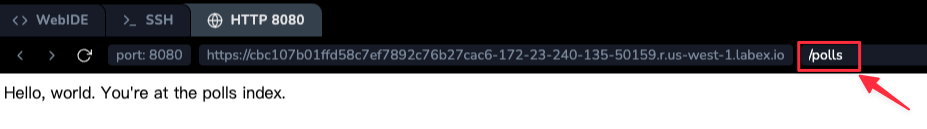

return HttpResponse("Hello, world. You're at the polls index.")This is the simplest view possible in Django. To call the view, we need to map it to a URL - and for this we need a URLconf.

To create a URLconf in the polls directory, create a file called urls.py. Your app directory should now look like:

polls/

__init__.py

admin.py

apps.py

migrations/

__init__.py

models.py

tests.py

urls.py

views.pyIn the polls/urls.py file include the following code:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path("", views.index, name="index"),

]The next step is to point the root URLconf at the polls.urls module. In mysite/urls.py, add an import for django.urls.include and insert an ~django.urls.include in the urlpatterns list, so you have:

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import include, path

urlpatterns = [

path("polls/", include("polls.urls")),

path("admin/", admin.site.urls),

]The ~django.urls.include function allows referencing other URLconfs. Whenever Django encounters ~django.urls.include, it chops off whatever part of the URL matched up to that point and sends the remaining string to the included URLconf for further processing.

The idea behind ~django.urls.include is to make it easy to plug-and-play URLs. Since polls are in their own URLconf (polls/urls.py), they can be placed under "/polls/", or under "/fun_polls/", or under "/content/polls/", or any other path root, and the app will still work.

When to use

~django.urls.include()

You should always useinclude()when you include other URL patterns.admin.site.urlsis the only exception to this.

You have now wired an index view into the URLconf. Verify it's working with the following command:

python manage.py runserver 0.0.0.0:8080Go to <http://index view.

The ~django.urls.path function is passed four arguments, two required: route and view, and two optional: kwargs, and name. At this point, it's worth reviewing what these arguments are for.

~django.urls.path argument: routeroute is a string that contains a URL pattern. When processing a request, Django starts at the first pattern in urlpatterns and makes its way down the list, comparing the requested URL against each pattern until it finds one that matches.

Patterns don't search GET and POST parameters, or the domain name. For example, in a request to https://www.example.com/myapp/, the URLconf will look for myapp/. In a request to https://www.example.com/myapp/?page=3, the URLconf will also look for myapp/.

~django.urls.path argument: viewWhen Django finds a matching pattern, it calls the specified view function with an ~django.http.HttpRequest object as the first argument and any "captured" values from the route as keyword arguments. We'll give an example of this in a bit.

~django.urls.path argument: kwargsArbitrary keyword arguments can be passed in a dictionary to the target view. We aren't going to use this feature of Django in the tutorial.

~django.urls.path argument: nameNaming your URL lets you refer to it unambiguously from elsewhere in Django, especially from within templates. This powerful feature allows you to make global changes to the URL patterns of your project while only touching a single file.

Congratulations! You have completed the Creation of a Basic Poll Application lab. You can practice more labs in LabEx to improve your skills.